DUST ON THE NETTLES

Exploring the life and works of poet Edward Thomas

Tuesday, 11 April 2017

Edward Thomas and the Tywi Valley

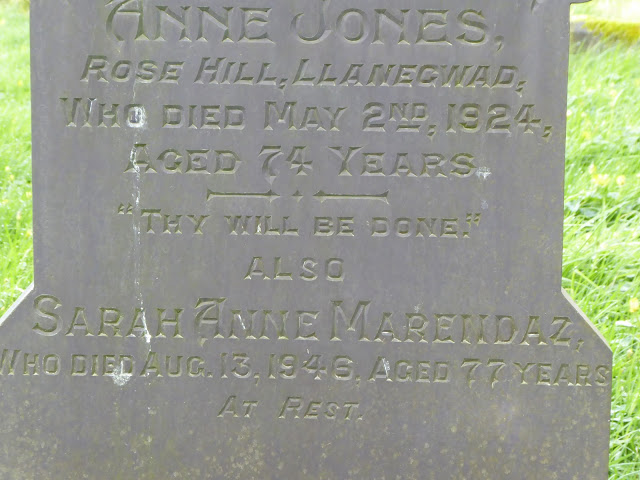

Several years ago I bought Edward Thomas' book "Wales". Imagine my surprise when reading, "And I have been to Abertillery, Pontypool, Caerleon, infernal Landore . . . . etc - and then "Nantgaredig". I did a double take. Amongst all the poetical Welsh place names - Myddfai, Llanddeusant, Llanddewi Brefi, Cil-y-Cwm - there was Nantgaredig. WHAT was it doing there? WHY did he mention it, for as it stands now it is just where the school is and the train station was and most people drive through it unless they live in Station Road. I pondered and then, when I was researching something else in our parish, my eye was drawn to the name Marendaz - Edward Thomas had Marendaz ancestors . . . The lady in the gravestone above (in Llanegwad churchyard), lived in the village for most of her life. She was down, aged 11, in the 1881 census. She was born in London, but her father was a Swansea man, and from what I deduced, he had married a Tywi Valley lass, who must have been working in Swansea. From what I remember, she died when Sarah Anne (put down simply as Ann Marendaz in the 1871 census) was very small and so the little girl went back to her maternal family roots. Nantgaredig was the station he would have left the train to walk the tracks across the fields to Llanegwad, to visit his Marendaz relative . . .

This ancient mounting block and equally ancient warty old tree beside it would definitely have been familiar to him, as would the cottage below when it was in its prime:

He would certainly have known Y Plas, which we tried to buy for my mum. When we viewed it the half timbering inside had every beam painted a different colour gloss, and there was someone dossing in the bedroom, but the original cloam fireplaces were still there from more than a century earlier. Now it is modernized, the beams covered in plaster and the clay fireplaces have long gone.

Dryslwyn Castle, dreaming across the fields.

He and Helen had spoken of moving to Wales - had he survived the war, perhaps they may have settled in the Tywi valley he knew and loved . . .

Sunday, 9 April 2017

The centenary of Edward Thomas's death

Blossom on the Damson tree; a clamour of birdsong; a trembling of Cowslips on a sunny bank; a blue mist of Bluebells deepening on the steep hillside. So will I remember the centenary of the death of Edward Thomas, who knew and loved the Towy Valley well and perhaps may have moved here with his family as he wanted to, had the war not intervened. For countryside such as this he gave his life . . .

Saturday, 1 April 2017

3th March 1917 - Letter from Edward Thomas to Eleanor Farjeon

Please forgive the extreme tardiness of my posts on here. At the moment thoughts on ET are uppermost again as I research a talk I have been asked to give on the Dymock Poets and his involvement in them.

As this is the centenary of his death, I thought it would be appropriate to remember him in a number of posts:

30th March 1917 - Edward Thomas to Eleanor Farjeon:

"My dear Eleanor, Another penultimate letter before I shall be unable to write from press of work. And first I must thank you for sending the apples and also for the apples themselves, which arrive today.

It was a good post, a parcel also from Mother and letters from Helen and Mother - there was one from you yesterday which I believe I must have answered. I have just looked at your letter again and I see you ask if I prefer things that can't be pooled. Perhaps I do, but perhaps I had better not. Everything is useful, and will be especially in the time to come when I have to take up food for perhaps considerably over 24 hours and pig it in noise and darkness and worse. Subalterns are told nothing but I happen to know what is intended, only not what difference this rain may make. I say this rain, but a most lovely cold bright evening, clear and still, has just passed, with many blackbirds singing. I fancy though that the Easter weather is not really beginning yet. I wish it was. I should welcome a warm night. Tomorrow I rather fear I shall have nowhere at all to shelter in, and no fire.

But nothing is so hard as the days of hanging about seeing that the men work like the one I had a day ago.

You will hear soon enough about what is doing, before I can tell you.

We have got a stray dog here, a big hairy brindled old thing, who likes us well and the fire too and stays in most of the time. Horton gives him bars of chocolate and often remarks that he's a lovely creature.

The town is catching it badly now and we are well away - touch wood - although we aren't in a paradise or the bagpipes wouldn't have played what they did last night. The crossings and corners are dirty places. But the Hun must be confounded with our numbers, though you might think he couldn't fire without hurting more than the open fields. Luckily he often does. He bangs away at one part (of ?) the beautiful grass and we can feel safe in another not far off. It isn't nice, though, going up in the cold dawn. If only one could keep warm without being burdened with clothes and all sorts of ornaments - glasses, maps, waterbottles, haversacks, gas-helmets, periscopes etc., so that a trenchcoat isn't wide enough, and if you have to throw yourself down you feel like an old woman home from marketing and still more so when you get up - while you on shore and a great many more are sleeping warm and dry-oh. Don't forget your old houseboat mate, Fol-de-rol-de-riddle-fol-de-rol-de-ri-do. Who is ever yours, Edward Thomas."

This latter fragment of sea-shanty was to remind Eleanor of a houseboat party in the summer of 1913, and says something of the pressure Edward and his batallion were under with a battle in the offing, and where his guard was briefly down, so that he tried to lighten his mood. Perhaps he had an inkling that they might be the last words he wrote to Eleanor, just as she had to accept they were just a short while later (he was to die in the Battle of Arras on 9th April 1917).

As this is the centenary of his death, I thought it would be appropriate to remember him in a number of posts:

30th March 1917 - Edward Thomas to Eleanor Farjeon:

"My dear Eleanor, Another penultimate letter before I shall be unable to write from press of work. And first I must thank you for sending the apples and also for the apples themselves, which arrive today.

It was a good post, a parcel also from Mother and letters from Helen and Mother - there was one from you yesterday which I believe I must have answered. I have just looked at your letter again and I see you ask if I prefer things that can't be pooled. Perhaps I do, but perhaps I had better not. Everything is useful, and will be especially in the time to come when I have to take up food for perhaps considerably over 24 hours and pig it in noise and darkness and worse. Subalterns are told nothing but I happen to know what is intended, only not what difference this rain may make. I say this rain, but a most lovely cold bright evening, clear and still, has just passed, with many blackbirds singing. I fancy though that the Easter weather is not really beginning yet. I wish it was. I should welcome a warm night. Tomorrow I rather fear I shall have nowhere at all to shelter in, and no fire.

But nothing is so hard as the days of hanging about seeing that the men work like the one I had a day ago.

You will hear soon enough about what is doing, before I can tell you.

We have got a stray dog here, a big hairy brindled old thing, who likes us well and the fire too and stays in most of the time. Horton gives him bars of chocolate and often remarks that he's a lovely creature.

The town is catching it badly now and we are well away - touch wood - although we aren't in a paradise or the bagpipes wouldn't have played what they did last night. The crossings and corners are dirty places. But the Hun must be confounded with our numbers, though you might think he couldn't fire without hurting more than the open fields. Luckily he often does. He bangs away at one part (of ?) the beautiful grass and we can feel safe in another not far off. It isn't nice, though, going up in the cold dawn. If only one could keep warm without being burdened with clothes and all sorts of ornaments - glasses, maps, waterbottles, haversacks, gas-helmets, periscopes etc., so that a trenchcoat isn't wide enough, and if you have to throw yourself down you feel like an old woman home from marketing and still more so when you get up - while you on shore and a great many more are sleeping warm and dry-oh. Don't forget your old houseboat mate, Fol-de-rol-de-riddle-fol-de-rol-de-ri-do. Who is ever yours, Edward Thomas."

This latter fragment of sea-shanty was to remind Eleanor of a houseboat party in the summer of 1913, and says something of the pressure Edward and his batallion were under with a battle in the offing, and where his guard was briefly down, so that he tried to lighten his mood. Perhaps he had an inkling that they might be the last words he wrote to Eleanor, just as she had to accept they were just a short while later (he was to die in the Battle of Arras on 9th April 1917).

Wednesday, 28 January 2015

Edwin Muir: The Horses

Edwin Muir was another contemporary of Edward Thomas's. He was born in Orkney, but later his parents moved to Glasgow, where he was very unhappy, having lost his parents and brothers in quick succession, and having to endure a series of awful jobs working in factories and offices, including one factory which turned bones into charcoal . . . Unsurprisingly he looked upon his Orkney childhood as idyllic and the dichotomy of his move to the city and unhappiness shaped his work as a poet.

THE HORSES by Edwin Muir

Barely a twelvemonth after

The seven days war that put the world to sleep,

Late in the evening the strange horses came.

By then we had made our covenant with silence,

But in the first few days it was so still

We listened to our breathing and were afraid.

On the second day

The radios failed; we turned the knobs; no answer.

On the third day a warship passed us, heading north,

Dead bodies piled on the deck. On the sixth day

A plane plunged over us into the sea. Thereafter

Nothing. The radios dumb;

And still they stand in corners of our kitchens,

And stand, perhaps, turned on, in a million rooms

All over the world. But now if they should speak,

If on a sudden they should speak again,

If on the stroke of noon a voice should speak,

We would not listen, we would not let it bring

That old bad world that swallowed its children quick

At one great gulp. We would not have it again.

Sometimes we think of the nations lying asleep,

Curled blindly in impenetrable sorrow,

And then the thought confounds us with its strangeness.

The tractors lie about our fields; at evening

They look like dank sea-monsters couched and waiting.

We leave them where they are and let them rust:

'They'll molder away and be like other loam.'

We make our oxen drag our rusty plows,

Long laid aside. We have gone back

Far past our fathers' land.

And then, that evening

Late in the summer the strange horses came.

We heard a distant tapping on the road,

A deepening drumming; it stopped, went on again

And at the corner changed to hollow thunder.

We saw the heads

Like a wild wave charging and were afraid.

We had sold our horses in our fathers' time

To buy new tractors. Now they were strange to us

As fabulous steeds set on an ancient shield.

Or illustrations in a book of knights.

We did not dare go near them. Yet they waited,

Stubborn and shy, as if they had been sent

By an old command to find our whereabouts

And that long-lost archaic companionship.

In the first moment we had never a thought

That they were creatures to be owned and used.

Among them were some half a dozen colts

Dropped in some wilderness of the broken world,

Yet new as if they had come from their own Eden.

Since then they have pulled our plows and borne our loads

But that free servitude still can pierce our hearts.

Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.

Acknowledging www.thepoemhunter.com from whence I copied the poem.

Sunday, 18 January 2015

An Ivor Gurney poem - I Saw England (July Night)

NOT England in this photo, but I wanted some sunshine! This is Valerian growing at New Quay, Cardiganshire, back in the summer.

I SAW ENGLAND (JULY NIGHT) by Ivor Gurney

She was a village

Of lovely knowledge

The high roads left her aside, she was forlorn, a maid -

Water ran there, dusk hid her, she climbed four-wayed,

Brown-gold windows showed last folk not yet asleep;

Water ran, was a centre of silence deep,

Fathomless deeps of pricked sky, almost fathomless

Hallowed an upward gaze in pale satin of blue,

And I was happy indeed, of mind, soul, body even

Having not given

A sign undoubtful of a dear England few

Doubt, not many have seen,

That Will Squele he knew and was so shriven,

Home of Twelth Night - Edward Thomas by Arras fallen,

Borrow and Hardy, Sussex tales out of Roman heights callen,

No madrigals or field-songs to my all reverent whim;

Till I got back I was dumb.

Although contemporaries, in poetry and as soldiers in WWI, I don't believe that Ivor Gurney and Edward Thomas ever met, yet Gurney had read ET's poetry, and in a short piece I have found in an article on the PN Review Online (which you have to be a member to access fully), thee is a quote about Thomas's poems from a letter Gurney wrote in November of 1917:

"Very curious they are, very interesting; nebulously intangibly beautiful. But he had the same sickness of mind I have - the impossibility of serenity for any but the shortest space. Such a mind produces little."

Gurney is suggesting that ET had the same mental instablility as Gurney - which saw him spent the latter half of his life in a mental asylum - he had self-diagnosed himself with neurasthenia. I have read that Thomas WAS diagnosed with the same complaint at some point, but it is perhaps best not to jump to the obvious conclusions. Thomas's poetry never really showed any imbalance in the way that Gurney's later poetry did. Perhaps his writing about "the other man" or other subliminal approaches in his poetry or prose suggested this to Gurney - who would recognize it, being a fellow sufferer?

I know that Edward Thomas's widow Helen went to visit Gurney from 1932 onwards when he was in the asylum and once took him a map of Gloucestershire (how thoughtful of her) which brought him alive in a way few other things could, apart from music, which was his first love and real talent. She kept up the meetings until his death from TB in 1937.

She wrote of their first meeting:

‘we were met by a tall gaunt dishevelled man clad in pyjamas and dressing gown, to whom Miss Scott introduced me. He gazed with an intense stare into my face and took me silently by the hand. Then I gave him the flowers which he took with the same deeply moving intensity and silence. He then said, ‘You are Helen, Edward’s wife and Edward is dead.’ And I said, ‘Yes, let us talk of him.’ (H. Thomas, Time and Again: Memoirs and Letters, ed. M. Thomas, 1978, pp. 11-112.) (This was copied from The Ivor Gurney Collection page - HERE.)

I SAW ENGLAND (JULY NIGHT) by Ivor Gurney

She was a village

Of lovely knowledge

The high roads left her aside, she was forlorn, a maid -

Water ran there, dusk hid her, she climbed four-wayed,

Brown-gold windows showed last folk not yet asleep;

Water ran, was a centre of silence deep,

Fathomless deeps of pricked sky, almost fathomless

Hallowed an upward gaze in pale satin of blue,

And I was happy indeed, of mind, soul, body even

Having not given

A sign undoubtful of a dear England few

Doubt, not many have seen,

That Will Squele he knew and was so shriven,

Home of Twelth Night - Edward Thomas by Arras fallen,

Borrow and Hardy, Sussex tales out of Roman heights callen,

No madrigals or field-songs to my all reverent whim;

Till I got back I was dumb.

Although contemporaries, in poetry and as soldiers in WWI, I don't believe that Ivor Gurney and Edward Thomas ever met, yet Gurney had read ET's poetry, and in a short piece I have found in an article on the PN Review Online (which you have to be a member to access fully), thee is a quote about Thomas's poems from a letter Gurney wrote in November of 1917:

"Very curious they are, very interesting; nebulously intangibly beautiful. But he had the same sickness of mind I have - the impossibility of serenity for any but the shortest space. Such a mind produces little."

Gurney is suggesting that ET had the same mental instablility as Gurney - which saw him spent the latter half of his life in a mental asylum - he had self-diagnosed himself with neurasthenia. I have read that Thomas WAS diagnosed with the same complaint at some point, but it is perhaps best not to jump to the obvious conclusions. Thomas's poetry never really showed any imbalance in the way that Gurney's later poetry did. Perhaps his writing about "the other man" or other subliminal approaches in his poetry or prose suggested this to Gurney - who would recognize it, being a fellow sufferer?

I know that Edward Thomas's widow Helen went to visit Gurney from 1932 onwards when he was in the asylum and once took him a map of Gloucestershire (how thoughtful of her) which brought him alive in a way few other things could, apart from music, which was his first love and real talent. She kept up the meetings until his death from TB in 1937.

She wrote of their first meeting:

‘we were met by a tall gaunt dishevelled man clad in pyjamas and dressing gown, to whom Miss Scott introduced me. He gazed with an intense stare into my face and took me silently by the hand. Then I gave him the flowers which he took with the same deeply moving intensity and silence. He then said, ‘You are Helen, Edward’s wife and Edward is dead.’ And I said, ‘Yes, let us talk of him.’ (H. Thomas, Time and Again: Memoirs and Letters, ed. M. Thomas, 1978, pp. 11-112.) (This was copied from The Ivor Gurney Collection page - HERE.)

Wednesday, 14 January 2015

TO E.T. by Robert Frost

A sideways step today, with a poem by Robert Frost, who was such a close friend of Edward Thomas's and gave him so much encouragement to become and stay a poet.

Looking across Llandyfeisant churchyard.

TO E.T.

I slumbered with your poems on my breast,

Spread open as I dropped them half-read through

Like dove wings on a figure on a tomb,

To see if in a dream they brought of you

I might not have the chance I missed in life

Through some delay, and call you to your face

First soldier, and then poet, and then both,

Who died a soldier-poet of your race.

I meant, you meant, that nothing should remain

Unsaid between us, brother, and this remained -

And one thing more that was not then to say:

The Victory for what is lost and gained.

You went to meet the shell's embrace of fire

On Vimy Ridge; and when you fell that day

The war seemed over more for you than me,

But now for me than you - the other way.

How over, though, for even me who knew

The foe thrust back unsafe beyond the Rhine;

If I was not to speak of it to you

And see you pleased once more with words of mine?

Robert Frost.

Looking across Llandyfeisant churchyard.

TO E.T.

I slumbered with your poems on my breast,

Spread open as I dropped them half-read through

Like dove wings on a figure on a tomb,

To see if in a dream they brought of you

I might not have the chance I missed in life

Through some delay, and call you to your face

First soldier, and then poet, and then both,

Who died a soldier-poet of your race.

I meant, you meant, that nothing should remain

Unsaid between us, brother, and this remained -

And one thing more that was not then to say:

The Victory for what is lost and gained.

You went to meet the shell's embrace of fire

On Vimy Ridge; and when you fell that day

The war seemed over more for you than me,

But now for me than you - the other way.

How over, though, for even me who knew

The foe thrust back unsafe beyond the Rhine;

If I was not to speak of it to you

And see you pleased once more with words of mine?

Robert Frost.

Monday, 12 January 2015

The Signpost by R S Thomas

I am going to try and post poetry regularly, Edward Thomas and his contemporaries. Here is R S Thomas, who is another addition to my poetry library.

THE SIGNPOST

Casgob, it said, 2

miles. But I never went

there; left it like an ornament

on the mind's shelf, covered

with the dust of

its summers; a place on a diet

of the echoes of stopped

bells and children's

voices; white the architecture

of its clouds, stationary

its sunlight. It was best

so, I need a museum

for storing the dream's

brittler particles in. Time

is a main road, eternity

the turning that we don't take.

THE SIGNPOST

Casgob, it said, 2

miles. But I never went

there; left it like an ornament

on the mind's shelf, covered

with the dust of

its summers; a place on a diet

of the echoes of stopped

bells and children's

voices; white the architecture

of its clouds, stationary

its sunlight. It was best

so, I need a museum

for storing the dream's

brittler particles in. Time

is a main road, eternity

the turning that we don't take.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)